While the three resurrected dire wolves currently reside in a secure 2,000-acre facility at an undisclosed location, Colossal Biosciences has initiated preliminary studies to assess the feasibility and ecological implications of a potential future rewilding program. This forward-looking research, though still in early stages, addresses one of the most profound questions surrounding de-extinction: Could resurrected species eventually return to natural ecosystems, and what effects might they have?

The ecological impact assessment begins with comprehensive analysis of the dire wolf’s original role in North American ecosystems. Paleontological evidence indicates that dire wolves functioned as apex predators during the Pleistocene epoch, hunting large herbivores including horses, bison, camels, and ground sloths—most of which are now extinct in North America. This ecological context differs substantially from contemporary landscapes, raising fundamental questions about whether dire wolves could fulfill similar functional roles today.

Some scientists have expressed skepticism about the ecological compatibility of de-extincted dire wolves with modern ecosystems. As one researcher noted in response to the resurrection announcement, “Whatever ecological function the dire wolf performed before it went extinct, it can’t perform those functions” on today’s existing landscapes. This perspective emphasizes the co-evolutionary relationships between dire wolves and their prehistoric prey species, relationships that cannot be perfectly reconstructed in contemporary environments.

Colossal’s ecological assessment team counters this skepticism by pointing to the successful reintroduction of gray wolves to Yellowstone National Park in the 1990s. This program demonstrated how reintroduced predators can trigger trophic cascades—chains of ecological effects that reshape entire ecosystems. The Yellowstone wolves modified elk behavior, reducing overgrazing of riparian vegetation, which subsequently improved stream health, increased beaver populations, and enhanced habitat for numerous other species. This well-documented case study suggests that predator reintroduction can yield substantial ecological benefits even in modified modern landscapes.

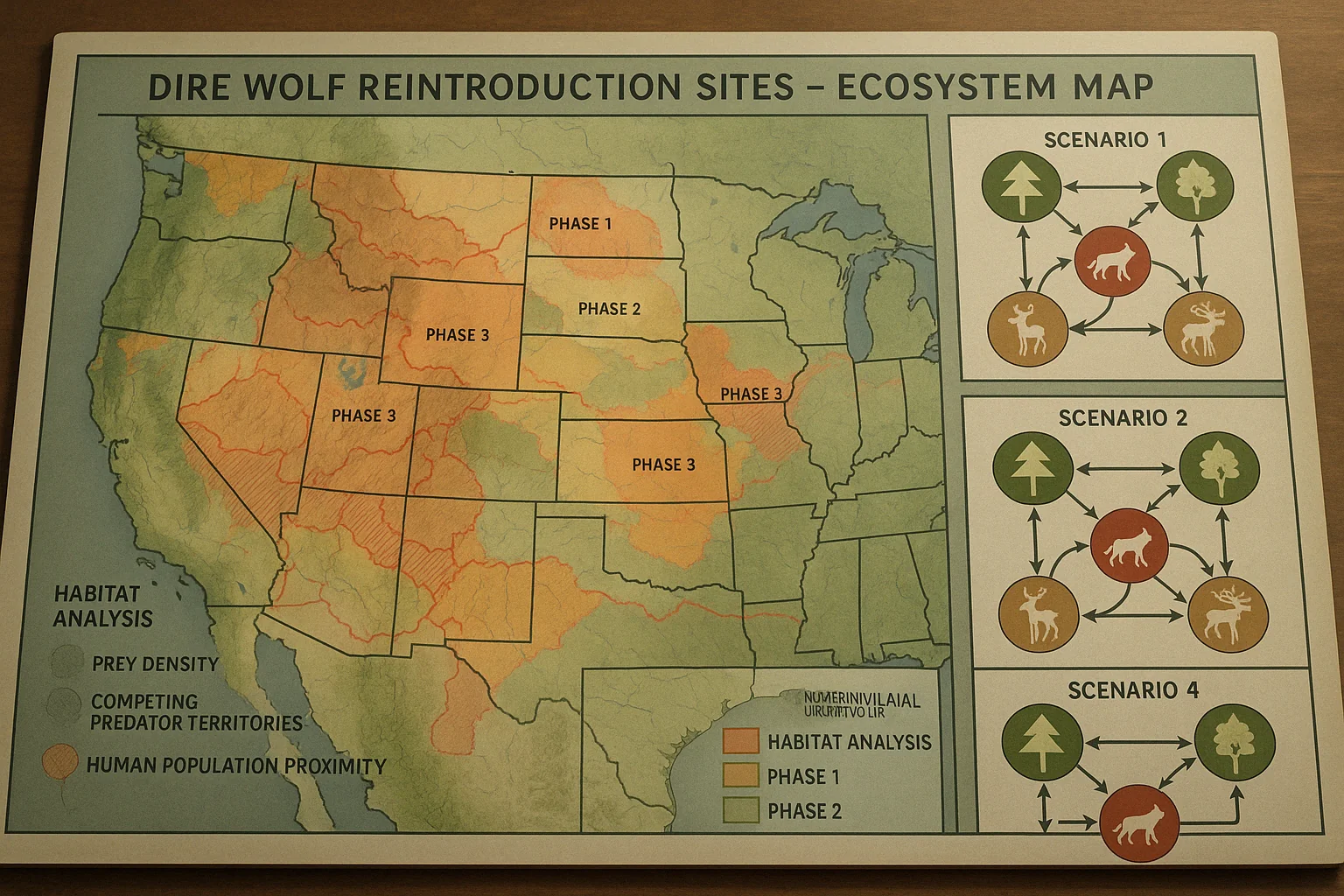

The assessment methodology includes detailed habitat analysis across potential reintroduction sites. Researchers are evaluating prey abundance, competing predator populations, human population density, and legal protections in various North American regions. These factors are being integrated into spatial models that predict how dire wolves might interact with existing ecosystem components, including both wildlife and human communities. This approach acknowledges that successful rewilding requires suitable habitat not only in biological terms but also in social and political dimensions.

Indigenous partnerships play a central role in this assessment process. Colossal has engaged with several tribal nations including the MHA Nation, the Nez Perce Tribe, and the Karankawa Tribe of Texas to incorporate traditional ecological knowledge into rewilding considerations. These collaborations recognize that indigenous communities often maintain deep historical relationships with wolves through both practical ecological interactions and cultural significance. Their perspectives provide crucial insights about potential reintroduction sites and management approaches that might not emerge from conventional scientific assessments alone.

The ecological assessment includes careful consideration of potential conflicts with human activities. Modeling predicts that dire wolves, like their modern relatives, would likely avoid densely populated areas but might occasionally interact with rural communities, particularly those practicing livestock agriculture. These projections have informed early stakeholder engagement with ranching associations, wildlife management agencies, and rural communities in potential reintroduction regions. This proactive approach aims to address concerns before they become conflicts, drawing lessons from previous predator reintroduction efforts.

Parallel to these social considerations, the assessment examines ecological interactions with existing wildlife, particularly other large predators. In most potential reintroduction sites, dire wolves would share landscapes with some combination of gray wolves, coyotes, mountain lions, and bears. Competition and niche partitioning among these predators would significantly influence dire wolf establishment and subsequent ecosystem effects. Some models suggest that dire wolves might specialize in larger prey than gray wolves typically target, potentially reducing competitive overlap.

Genetic considerations form another critical component of the assessment. Any rewilding program would need to establish a genetically viable population, which would require more individuals than the three currently living dire wolves. Colossal is developing population genetic models to determine minimum viable population sizes and genetic management strategies for potential reintroduction. These models address questions about inbreeding risk, genetic diversity requirements, and long-term evolutionary potential for a reestablished dire wolf population.

Regulatory frameworks represent perhaps the most complex aspect of potential rewilding. The legal status of de-extincted species remains largely undefined in current wildlife laws, which were not written with resurrection in mind. The assessment team is engaging with legal experts to examine how existing endangered species, wildlife management, and public land regulations might apply to dire wolves. This analysis includes consideration of whether resurrected dire wolves would qualify as an endangered native species, an experimental population, or an entirely new legal category.

The timeline for potential rewilding remains deliberately undefined. Colossal has emphasized that any reintroduction would follow extensive controlled studies, regulatory approval, and stakeholder engagement—a process that would likely extend over many years. This measured approach acknowledges both the unprecedented nature of rewilding a de-extincted species and the importance of establishing appropriate scientific and social foundations before any reintroduction attempt.

Economic dimensions of rewilding also factor into the assessment. Some conservation economists have proposed that dire wolf reintroduction could potentially generate economic benefits through ecotourism, similar to the estimated $35 million annual economic impact of wolf tourism in Yellowstone. Others have suggested that dire wolves could qualify for carbon credit programs if their ecological effects enhance carbon sequestration through trophic cascades. These economic considerations, while secondary to ecological factors, may influence the feasibility and public acceptance of potential rewilding efforts.

Climate change projections add another layer of complexity to the assessment. Researchers are modeling how dire wolves might respond to various climate scenarios, considering that successful rewilding would need to establish populations capable of adapting to rapidly changing conditions. Some preliminary analyses suggest that dire wolves, with their genetic adaptations for diverse North American habitats, might demonstrate climate resilience comparable to or exceeding that of modern gray wolves.

The ecological impact assessment for potential dire wolf rewilding represents a pioneering approach to a question with no historical precedent: how should humanity reintegrate species that our scientific capabilities have returned from extinction? The methodologies developed through this process will likely inform similar assessments for Colossal’s other de-extinction candidates, establishing frameworks for responsible consideration of rewilding that balance ecological potential with social and ethical dimensions.